Sandbox

Politics and porn (What's the matter with Kansas?)

Distrust your data

by Jacob Harris, opennews.org, 22 May 2014

Harris identifies 6 ways to make mistakes in reporting data:

- Sloppy proxieson

- Dichotomizing

- Correlation does not equal causation

- Ecological inference

- Geocoding

- Data naivete

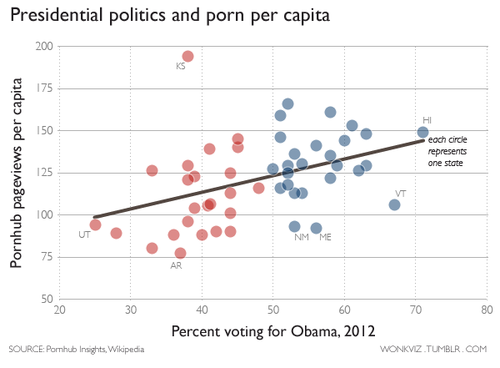

His prime example is a story that was widely circulated via social media, featuring the following scatterplot

Kansas is a clear outlier. Harris credits a reader of Andrew Sullivan's blog for the following explanation of the geocoding problem:

What happened here was that a large percentage of IP addresses could not be resolved to an address any more specific than “USA.” When that address was geocoded, it returned a point in the centroid of the continental United States, which placed it in the state of—you guessed it—Kansas!

Kansas aside, the red/blue divide is still striking. The "ecological fallacy" here is similar to Durkheim's (see Chance News 92 here for more discussion), where he noted that the more Protestant the Prussian province, the larger the suicide rate--but it turns out that the suicides were actually committed by Catholics, not Protestants. The possible analogy here: in Democratic states it may be the Republicans who are frequenting pornography web sites.

More commentary can be found on Andrew Gelman's blog.

Submitted by Paul Alper

Confusion about odds

When spell-check can’t help

By Philip B. Corbett, "After Deadline" blog, New York Times, 13 May 2014

The After Deadline blog presents stylistic advice for journalists using examples from recent news stories. The present installment includes warnings about vague statements involving odds. Consider these two examples:

- The odds of Mr. Gandhi’s becoming the next prime minister have dropped so low that Mumbai bookies have stopped taking bets on him.

- [Headline] Iraq Unrest Narrows Odds for Maliki to Keep Seat

Corbett writes:

Take care to be clear in referring to “odds.” “Higher” odds could suggest that something is more likely (higher probability) or less likely (1,000 to 1, say, compared with 10 to 1). It was difficult to tell whether “narrows odds” in the second headline meant he had more chance or less. Consider “probability,” “likelihood” or “chance” as alternatives if “odds” might be ambiguous.

On a related note Paul Alper shared the following quotations from What the Numbers Say: A Field Guide to Mastering Our Numerical World by Derrick Niederman and David Boyum (p. 174):

- "If Congress ever decided to act in the public interest, it could do no worse than to pass a law banning the use of odds as a method for stating probabilities."

- "If you're confused [about odds], don't worry, for even if you understand how odds work, you can never be sure if the person you're talking to does."

Submitted by Bill Peterson