Sandbox: Difference between revisions

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

Wolfers reports on how badly the pollsters did on Scotland's referendum: pollsters predicted a very close result but was in the end there was actually a ten point difference. | Wolfers reports on how badly the pollsters did on Scotland's referendum: pollsters predicted a very close result but was in the end there was actually a ten point difference. | ||

He writes, "Typically, asking people who they think will win [http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/02/us/politics/a-better-poll-question-to-predict-the-election.html yields better forecasts], possibly because it leads them to also reflect on the opinions of those around them, and perhaps also because it may yield more honest answers. ...Indeed, in giving their expectations, some respondents may even reflect on whether or not they believe recent polling." | He writes, "Typically, asking people who they think will win [http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/02/us/politics/a-better-poll-question-to-predict-the-election.html yields better forecasts], possibly because it leads them to also reflect on the opinions of those around them, and perhaps also because it may yield more honest answers. ...Indeed, in giving their expectations, some respondents may even reflect on whether or not they believe recent polling." | ||

Margaret Cibes also sent links to this and also a pre-election piece by the same author: | |||

[http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/09/upshot/betting-markets-not-budging-over-poll-on-scottish-independence.html?_r=0 Betting markets not budging over poll on Scottish independence]<br> | |||

by Justin Wolfers, "The Upshot" blog, ''New York Times'', 8 September 2014 | |||

At that time, a new opinion poll had just predicted a win for the independence movement, a result which upset British financial markets. Wolfers wrote: | |||

<blockquote> | |||

The fast-moving news cycle may further shift public opinion — whether it’s recent promises for greater autonomy if the Scots remain within Britain or the announcement of another royal pregnancy. These broader uncertainties are never included in the so-called “margin of error” that comes with these polls. | |||

<br><br> | |||

But political prediction markets, in which people bet on the likely outcome, are all about evaluating and quantifying the full range of risks. And currently, bettors aren’t buying into the pro-independence hype. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

==Some math doodles== | ==Some math doodles== | ||

Revision as of 20:13, 21 September 2014

Scotland's independence referendum

There has been a lot of news surrounding the Scottish referendum. Paul Alper sent this

Scotland’s ‘No’ vote: A loss for pollsters and a win for betting markets

by Justin Wolfers, "The Upshot" blog, New York Times, 19 September 2014

Wolfers reports on how badly the pollsters did on Scotland's referendum: pollsters predicted a very close result but was in the end there was actually a ten point difference. He writes, "Typically, asking people who they think will win yields better forecasts, possibly because it leads them to also reflect on the opinions of those around them, and perhaps also because it may yield more honest answers. ...Indeed, in giving their expectations, some respondents may even reflect on whether or not they believe recent polling."

Margaret Cibes also sent links to this and also a pre-election piece by the same author:

Betting markets not budging over poll on Scottish independence

by Justin Wolfers, "The Upshot" blog, New York Times, 8 September 2014

At that time, a new opinion poll had just predicted a win for the independence movement, a result which upset British financial markets. Wolfers wrote:

The fast-moving news cycle may further shift public opinion — whether it’s recent promises for greater autonomy if the Scots remain within Britain or the announcement of another royal pregnancy. These broader uncertainties are never included in the so-called “margin of error” that comes with these polls.

But political prediction markets, in which people bet on the likely outcome, are all about evaluating and quantifying the full range of risks. And currently, bettors aren’t buying into the pro-independence hype.

Some math doodles

<math>P \left({A_1 \cup A_2}\right) = P\left({A_1}\right) + P\left({A_2}\right) -P \left({A_1 \cap A_2}\right)</math>

Accidental insights

My collective understanding of Power Laws would fit beneath the shallow end of the long tail. Curiosity, however, easily fills the fat end. I long have been intrigued by the concept and the surprisingly common appearance of power laws in varied natural, social and organizational dynamics. But, am I just seeing a statistical novelty or is there meaning and utility in Power Law relationships? Here’s a case in point.

While carrying a pair of 10 lb. hand weights one, by chance, slipped from my grasp and fell onto a piece of ceramic tile I had left on the carpeted floor. The fractured tile was inconsequential, meant for the trash.

As I stared, slightly annoyed, at the mess, a favorite maxim of the Greek philosopher, Epictetus, came to mind: “On the occasion of every accident that befalls you, turn to yourself and ask what power you have to put it to use.” Could this array of large and small polygons form a Power Law? With curiosity piqued, I collected all the fragments and measured the area of each piece.

| Piece | Sq. Inches | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43.25 | 31.9% |

| 2 | 35.25 | 26.0% |

| 3 | 23.25 | 17.2% |

| 4 | 14.10 | 10.4% |

| 5 | 7.10 | 5.2% |

| 6 | 4.70 | 3.5% |

| 7 | 3.60 | 2.7% |

| 8 | 3.03 | 2.2% |

| 9 | 0.66 | 0.5% |

| 10 | 0.61 | 0.5% |

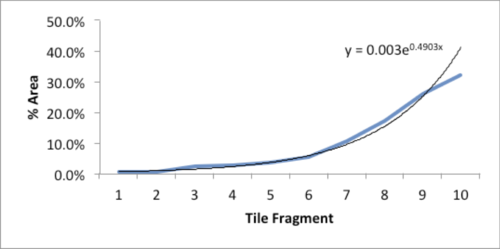

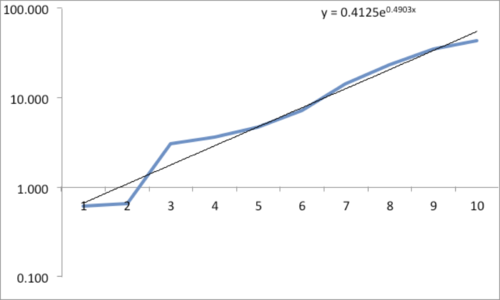

The data and plot look like a Power Law distribution. The first plot is an exponential fit of percent total area. The second plot is same data on a log normal format. Clue: Ok, data fits a straight line. I found myself again in the shallow end of the knowledge curve. Does the data reflect a Power Law or something else, and if it does what does it reflect? What insights can I gain from this accident? Favorite maxims of Epictetus and Pasteur echoed in my head: “On the occasion of every accident that befalls you, remember to turn to yourself and inquire what power you have to turn it to use” and “Chance favors only the prepared mind.”

My “prepared” mind searched for answers, leading me down varied learning paths. Tapping the power of networks, I dropped a note to Chance News editor Bill Peterson. His quick web search surfaced a story from Nature News on research by Hans Herrmann, et. al. Shattered eggs reveal secrets of explosions. As described there, researchers have found power-law relationships for the fragments produced by shattering a pane of glass or breaking a solid object, such as a stone. Seems there is a science underpinning how things break and explode; potentially useful in Forensic reconstructions. Bill also provided a link to a vignette from CRAN describing a maximum likelihood procedure for fitting a Power Law relationship. I am now learning my way through that.

Submitted by William Montante