Chance News 100: Difference between revisions

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

'''Con:''' "Those at the ceremony were the commodore, the fleet captain, the donor of the cup, Mr. Smith, and Mr. Jones."<br> | '''Con:''' "Those at the ceremony were the commodore, the fleet captain, the donor of the cup, Mr. Smith, and Mr. Jones."<br> | ||

This example from the 1934 style book of the New York Herald Tribune shows how a comma before "and" can result in a lack of clarity. With the comma, it reads as if Mr. Smith was the donor of the cup, which he was not. | This example from the 1934 style book of the ''New York Herald Tribune'' shows how a comma before "and" can result in a lack of clarity. With the comma, it reads as if Mr. Smith was the donor of the cup, which he was not. | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

Revision as of 18:14, 25 July 2014

Quotations

"Steve Ziliak, a critic of RCTs [randomised controlled trials], complains about one conducted in China in which some visually-impaired children were given glasses while others received nothing. The case against the trial is that we no more need a randomised trial of spectacles than we need a randomised trial of the parachute."

Submitted by Paul Alper

Forsooth

One sentence too many?

“At issue was how highly correlated the prices of various subprime mortgage bonds inside a CDO might be. Possible answers ranged from 0 percent (their prices had nothing to do with each other) to 100 percent (their prices moved in lockstep with each other). Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s judged the pools of triple-B-rated bonds to have a correlation of around 30 percent, which did not mean anything like what it sounds. It does not mean, for example, that if one goes bad, there is a 30 percent chance that the others will go bad too. It means that if one bond goes bad, the others experience very little decline at all.”

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

“When confronted with data from the Centers for Disease Control that seemed to provide scientific refutation of her claims [that vaccines caused autism, Jenny] McCarthy responded, ‘My science is named Evan [her son] and he’s at home. That’s my science.’ …. She is fond of saying that she acquired her knowledge of vaccinations and their risks at ‘the University of Google.’” [p. 79]

“[Dr. Andrew] Weil doesn’t buy into the idea that clinical evidence is more valuable than intuition. Like most practitioners of alternative medicine, he regards the scientific preoccupation with controlled studies, verifiable proof, and comparative analysis as petty and one dimensional.” [p. 257]

"[T]he National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine is the brainchild of Iowa senator Tom Harkin, who was inspired by his conviction that taking bee pollen cured his allergies …. There is no evidence that bee pollen cures allergies or lessens their symptoms. ….

In Senate testimony in March 2009, Harkin said he was disappointed in the work of the center because it had disproved too many alternative therapies. ‘One of the purposes of this center was to investigate and validate alternative approaches. Quite frankly, I must say publicly that it has fallen short,’ Harken said.” [pp. 174, 180]

“I don’t have either APOE4 allele, which is a great relief. ‘You dodged a bullet,’ my extremely wise physician said when I told him the news. ‘But don’t forget they might be coming out of a machine gun.” [p. 220]

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

"Another example of that interest was data from TiVo showing that although four of the top five streamed games of the tournament in homes with TiVo DVRs involved the United States team, six of the 10 most-streamed games involved teams from other countries." [One must bear in mind that the US played in exactly four games in the World Cup!]

Submitted by David Czerwinski

"The point is that just because one event sometimes follows another it does not follow that the following event is caused by that by which it is preceded. That this fallacy does, in fact, regularly get past your average journalist entitles it to a name: the post hoc, passed back fallacy."

"If only they could invent a drug that would cure journalistic impotence and permit hacks to have some meaningful intercourse with science. Now there would be a medical breakthrough."

Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 109

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

The Oxford comma: A pressing issue?

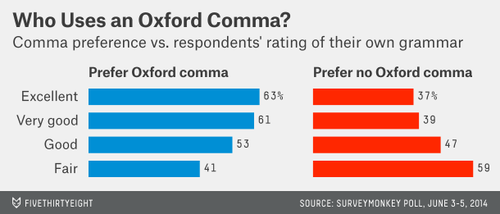

Elitist, superfluous, Or popular? We polled Americans on the Oxford comma

By Walt Hickey, FiveThirtyEight, 17June 2014

A grammatical point of controversy: should you use a comma before the "and" in a list of more than two items? As reported in the article:

We asked respondents which sentence was, in their opinion, more grammatically correct: “It’s important for a person to be honest, kind and loyal.” Or: “It’s important for a person to be honest, kind, and loyal.” The latter has an Oxford comma, the former none.

Among 1129 Americans responding, the Oxford comma was preferred, 57% to 43%. Interestingly, those in favor tended to have a higher opinion of their own grammatical skills, as shown in the accompanying graph

Lest you get the impression that this is simply a matter of taste, see The best shots fired in the Oxford comma wars. Among the amusing examples there:

Pro: "She took a photograph of her parents, the president, and the vice president."

This example from the Chicago Manual of Style shows how the comma is necessary for clarity. Without it, she is taking a picture of two people, her mother and father, who are the president and vice president. With it, she is taking a picture of four people.

Con: "Those at the ceremony were the commodore, the fleet captain, the donor of the cup, Mr. Smith, and Mr. Jones."

This example from the 1934 style book of the New York Herald Tribune shows how a comma before "and" can result in a lack of clarity. With the comma, it reads as if Mr. Smith was the donor of the cup, which he was not.

Submitted by Paul Alper

Interpreting climate change probabilities

Bob Griffin sent a link to the following

- The interpretation of IPCC probabilistic statements around the world

- by David V. Budescu, et al, Nature Climate Change, 20 April 2014

which he describes as "an intriguing look at how folks in different cultures around the world interpret the verbal statements of uncertainty that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change uses. They found that an alternative presentation format (verbal terms with numerical ranges) improves the correspondence between the IPCC guidelines and public interpretations. The alternative presentation format also produces more stable results across cultures."

On the Nature site, only the abstract is available to non subscribers, but you can read more about the study design in this Fordham University press release. As described there:

The study asked over 11,000 volunteers in 24 countries (and in 17 different languages) to provide their interpretations of a the intended meaning and possible range of 8 sentences form the IPCC report that included the various phrases. For example, one sentence read: “It is very likely that hot extremes, heat waves, and heavy precipitation events will continue to become more frequent.” Only a small minority of the participants interpreted the probability of that statement consistent with IPCC guidelines (over 90 percent), and the vast majority interpreted the term to convey a probability in around 70 percent.

A similar effect was observed with other phrases: When verbal descriptions were given without numerical ranges, readers tended to interpret the probabilities as being closer to 50 percent than intended by the guidelines.

The Wikipedia entry on Words of estimative probability provides some perspective on this, illustrating that different verbal descriptions are used in different fields. The phrase "words of estimative probability" (WEP) is described as originating in the intelligence community. (The lack of preparation prior to the 9/11 attacks is cited as a famous failure in risk communication.) But as described here, a different set of phrases are used in the medical community in the context of informed patient decision making.

Summer reading

Past, Present, and Future of Statistical Science, Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2014

This free pdf download is the result of a project of the Committee of Presidents of Statistical Societies (COPSS) to assemble from almost 50 statisticians their reminiscences, personal reflections, and perspectives on the discipline and profession, as well as advice for the next generation. The contributions are relatively short, very good reads.

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

Probability of precipitation

John Emerson sent a link to the following:

Pop quiz: 20 percent chance of rain. Do you need an umbrella?

“All Things Considered,” NPR, 22 July 2014

This is part of a weeklong series on NPR, called Risk and reason, that explores people's understanding of chance. Noting that weather forecasts represent an almost daily encounter with probability statements, NPR interviewers set out to explore what the person in the street understands by the phrase “20 percent chance of rain.” You can listen to some responses in the audio segment (about 7.5 minutes) provided at the above link, or read the synopsis there. Not surprisingly, there a variety of answers, most not very scientific.

NPR listeners pointed out the the segment itself failed to produce a succinct answer, so NPR produced a short followup story the next day Confusion with a chance of clarity: Your weather questions, answered (23 July 2014). Included there were descriptions from two meteorology experts. Eli Jacks, of the National Weather Service said:

There's a 20 percent chance that at least one-hundreth of an inch of rain — and we call that measurable amounts of rain — will fall at any specific point in a forecast area.

Jason Samenow, of the Capital Weather Gang at the Washington Post offered this:

It simply means for any locations for which the 20 percent chance of rain applies, measurable rain (more than a trace) would be expected to fall in two of every 10 weather situations like it.

More detailed discussion can be found at this FAQ page from NOAA, where we read

Mathematically, PoP [probability of precipitation] is defined as follows:

- PoP = C x A where "C" = the confidence that precipitation will occur somewhere in the forecast area, and where "A" = the percent of the area that will receive measureable precipitation, if it occurs at all.

Discussion

Are the two weather experts quoted above saying the same thing? Do their descriptions square with the mathematical definition?