Sandbox: Difference between revisions

| Line 112: | Line 112: | ||

:[http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2015/apr/23/did-we-lose-war-poverty-ii/ Did we lose the war on poverty?—II], 23 April 2015 | :[http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2015/apr/23/did-we-lose-war-poverty-ii/ Did we lose the war on poverty?—II], 23 April 2015 | ||

While not | While not disputing Jenks's main thesis that the poor are not faring well, the letters from Brigham and Robertson both fault his presentation of percentages. From Brigham: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

Professor Jencks (or his cited source) seems to have made the freshman error of confusing ''percentage points'' with ''percentage'' [“Did We Win the War on Poverty?—II,” NYR, April 23]. Rather than the bottom quarter of the income distribution having half the increase of the top quarter in college admissions, by the figures cited they had a 36 percent increase versus a 29 percent increase. That error is repeated further on vis-à-vis college graduation rates. Again, the bottom quarter did not have half the increase as the top but, rather, exactly the same: 14 percent. | Professor Jencks (or his cited source) seems to have made the freshman error of confusing ''percentage points'' with ''percentage'' [“Did We Win the War on Poverty?—II,” NYR, April 23]. Rather than the bottom quarter of the income distribution having half the increase of the top quarter in college admissions, by the figures cited they had a 36 percent increase versus a 29 percent increase. That error is repeated further on vis-à-vis college graduation rates. Again, the bottom quarter did not have half the increase as the top but, rather, exactly the same: 14 percent. | ||

Revision as of 15:36, 15 September 2015

More on the hot hand

In Chance News 105, the last item was titled Does Selection bias explain the hot hand?. It described how in their July 6 article, Miller and Sanjurjo assert that a way to determine the probability of a heads following a heads in a fixed sequence, you may calculate the proportion of times a head is followed by a head for each possible sequence and then compute the average proportion, giving each sequence an equal weighting on the grounds that each possible sequence is equally likely to occur. I agree that each possible sequence is equally likely to occur. But I assert that it is illegitimate to weight each sequence equally because some sequences have more chances for a head to follow a second head than others.

Let us assume, as Miller and Sanjurjo do, that we are considering the 14 possible sequences of four flips containing at least one head in the first three flips. A head is followed by another head in only one of the six sequences (see below) that contain only one head that could be followed by another, making the probability of a head being followed by another 1/6 for this set of six sequences.

TTHT Heads follows heads 0 time. THTT Heads follows heads 0 times HTTT Heads follows heads 0 times TTHH Heads follows heads 1 time THTH Heads follows heads 0 times HTTH Heads follows heads 0 times

A head is followed by another head six times in the six sequences (see below) that contain two heads that could be followed by another head, making the probability of a head being followed by another 6/12 = 1/2 for this set of six sequences.

THHT Heads follows heads 1 time HTHT Heads follows heads 0 times HHTT Heads follows heads 1 time THHH Heads follows heads 2 times HTHH Heads follows heads 1 time HHTH Heads follows heads 1 time

A head is followed by another head five times in the six sequences (see below) that contain three heads that could be followed by another head, making the probability of a head being followed by another 5/6 this set of two sequences.

HHHT Heads follows heads 2 times HHHH Heads follows heads 3 times

An unweighted average of the 14 sequences gives

[(6 × 1/6) + (6 × 1/2) + (2 × 5/6)] / 14 = [17/3] / 14 = 0.405,

which is what Miller and Sanjurjo report. A weighted average of the 14 sequences gives

[(1)(6 × 1/6) + (2)(6 × 1/2) + (3)(2 × 5/6)] / [(1×6) + (2 × 6) + (3 × 2)]

= [1 + 6 + 5] / [6 + 12 + 6] = 12/24 = 0.50.

Using an unweighted average instead of a weighted average is the pattern of reasoning underlying the statistical artifact known as Simpson’s paradox. And as is the case with Simpson’s paradox, it leads to faulty conclusions about how the world works.

Submitted by Jeff Eiseman, University of Massachusetts

Comment

| Sequence of tosses |

Number of H in first 3 tosses |

Number of H followed by H |

Number of HH in first 3 tosses |

Number of HH followed by H |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTTT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TTTH | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TTHT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| THTT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HTTT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TTHH | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| THTH | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| THHT | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| HTTH | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HTHT | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HHTT | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| THHH | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| HTHH | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| HHTH | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| HHHT | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| HHHH | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 24 | 12 | 8 | 4 |

Percent change vs. percentage point change

Mike Olinick sent a link to the following exchange:

- The poor in college

- by John S. Bowman, William Brigham, and Frank Robertson, The New York Review of Books, 4 June 2015

These are responses to two earlier NYR articles by Christopher Jenks:

- The war on poverty: Was it lost?, 2 April 2015

- Did we lose the war on poverty?—II, 23 April 2015

While not disputing Jenks's main thesis that the poor are not faring well, the letters from Brigham and Robertson both fault his presentation of percentages. From Brigham:

Professor Jencks (or his cited source) seems to have made the freshman error of confusing percentage points with percentage [“Did We Win the War on Poverty?—II,” NYR, April 23]. Rather than the bottom quarter of the income distribution having half the increase of the top quarter in college admissions, by the figures cited they had a 36 percent increase versus a 29 percent increase. That error is repeated further on vis-à-vis college graduation rates. Again, the bottom quarter did not have half the increase as the top but, rather, exactly the same: 14 percent.

From Robertson:

Jencks states that the percentage of upper-income students entering college rose from 51 to 66 percent between 1972 and 1992, while the percentage of low income students rose from 22 to 30 percent, “only about half as much.” However, the percentage increase needs to be calculated as a percentage of the starting figure. It is not simply the subtraction of the start from the final. Thus, the percentage increase of low-income students is actually 8/22, or 36 percent, while the increase among upper income students is 15/51, or only 29 percent. The error is repeated in Jencks’s discussion of graduation rates.

Some math doodles

<math>P \left({A_1 \cup A_2}\right) = P\left({A_1}\right) + P\left({A_2}\right) -P \left({A_1 \cap A_2}\right)</math>

<math>\hat{p}(H|H)</math>

<math>\hat{p}(H|HH)</math>

Accidental insights

My collective understanding of Power Laws would fit beneath the shallow end of the long tail. Curiosity, however, easily fills the fat end. I long have been intrigued by the concept and the surprisingly common appearance of power laws in varied natural, social and organizational dynamics. But, am I just seeing a statistical novelty or is there meaning and utility in Power Law relationships? Here’s a case in point.

While carrying a pair of 10 lb. hand weights one, by chance, slipped from my grasp and fell onto a piece of ceramic tile I had left on the carpeted floor. The fractured tile was inconsequential, meant for the trash.

As I stared, slightly annoyed, at the mess, a favorite maxim of the Greek philosopher, Epictetus, came to mind: “On the occasion of every accident that befalls you, turn to yourself and ask what power you have to put it to use.” Could this array of large and small polygons form a Power Law? With curiosity piqued, I collected all the fragments and measured the area of each piece.

| Piece | Sq. Inches | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43.25 | 31.9% |

| 2 | 35.25 | 26.0% |

| 3 | 23.25 | 17.2% |

| 4 | 14.10 | 10.4% |

| 5 | 7.10 | 5.2% |

| 6 | 4.70 | 3.5% |

| 7 | 3.60 | 2.7% |

| 8 | 3.03 | 2.2% |

| 9 | 0.66 | 0.5% |

| 10 | 0.61 | 0.5% |

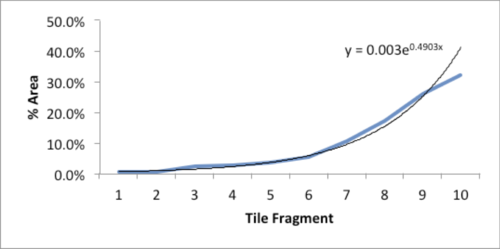

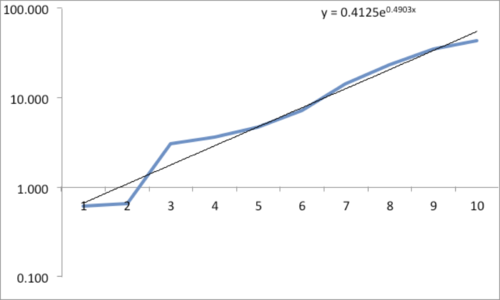

The data and plot look like a Power Law distribution. The first plot is an exponential fit of percent total area. The second plot is same data on a log normal format. Clue: Ok, data fits a straight line. I found myself again in the shallow end of the knowledge curve. Does the data reflect a Power Law or something else, and if it does what does it reflect? What insights can I gain from this accident? Favorite maxims of Epictetus and Pasteur echoed in my head: “On the occasion of every accident that befalls you, remember to turn to yourself and inquire what power you have to turn it to use” and “Chance favors only the prepared mind.”

My “prepared” mind searched for answers, leading me down varied learning paths. Tapping the power of networks, I dropped a note to Chance News editor Bill Peterson. His quick web search surfaced a story from Nature News on research by Hans Herrmann, et. al. Shattered eggs reveal secrets of explosions. As described there, researchers have found power-law relationships for the fragments produced by shattering a pane of glass or breaking a solid object, such as a stone. Seems there is a science underpinning how things break and explode; potentially useful in Forensic reconstructions. Bill also provided a link to a vignette from CRAN describing a maximum likelihood procedure for fitting a Power Law relationship. I am now learning my way through that.

Submitted by William Montante